Is music a cultural social asset or is it noise? The schism in Victorian music policy and regulation.

By Jon Perring

There is a schism in Government Policy as it tries to wrangle live music. There are two conflicting approaches taken between the Victorian Planning Scheme’s provisions – the VPP - and the EPA’s environmental noise regulations.

The Planning scheme’s stated purpose relating to live music are:

· “To recognise that live music is an important part of the State’s culture and economy.

· To encourage the retention of existing and the development of new live music entertainment venues.

· To protect live music entertainment venues from the encroachment of noise sensitive residential uses.

· To ensure that noise sensitive residential uses are satisfactorily protected from unreasonable levels of live music and entertainment noise.

· To ensure that the primary responsibility for noise attenuation rests with the agent of change.”

However, at a closer read, these environmental noise regulations are riddled with pejorative terms and characterise music as ‘noise’ (unwanted sound) whilst likening its practice not to producing an important part of our culture but as an alternative to boredom, as ‘entertainment’.

Where the Victorian Planning Scheme seeks to balance access to live music with a resident’s right to sleep and enjoyment of their home, it also protects other sensitive uses such as Child Care, residential institutions, hospitals, etc. Simply put, the VPP balances competing uses without judgment.

In the recent discussion paper, Better Environment Protection Approvals for

Outdoor Events from the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (October 2025), the paper mentions Noise pollution 33 times, Music noise 113 times, and culture twice. Noise is mentioned 458 times, and Music 225 times. This tells us a lot about how the paper approaches the regulation of music in our society and what value it puts on it.

The paper focuses on the regulation that requires attention to reduce red tape. There is no doubt that exemptions are needed, but because of its inherent bias against the value of music, it’s fundamental to understanding the current dysfunction in the context of the regulation’s inherent contradictions.

Let’s be clear!

Music is not noise pollution; it is sound.

However, the EPA’s noise regulations frame music as noise.

Sound is a neutral description of the material that occurs in the environment, and the correct term to be used. It has several types:

Biophonic – living organisms such as animal sounds,

Geophony - weather, sea, etc

Anthropophony – human-generated sounds of which, for our purpose, fall into two types: machine and cultural sound.

Machine noise has its own set of Environmental control standards and regulations. It’s well covered, so we don’t need to concern ourselves with these regulations. All sound generated by machines can be characterised as noise. Therefore, all attempts to mitigate machine noise can be regarded as a public good. Interestingly, the most significant sources of environmental noise by far are transport noise (traffic, aircraft, trains, and trams) and construction noise. Neither of which is covered by the EPA’s environmental noise regulations.

Music is a major component of Cultural Sound and can’t be universally considered noise, as it depends on the context and each person’s point of view as to whether it is considered noise or, a valued cultural product of our society. Of course, a person’s point of view is informed by the genre of music it is, who is playing it and, who is listening to it (the cultural or subcultural grouping), as well as the time it is being played, how long it has been going on, and how loud it is. The characterisation of music as noise is subjective.

The EPA’s definition of Aggravate Music Noise for outdoor events and indoor venues is when the sound level is excessive at a sensitive use location. The EPA can issue fines, and the police can shut down the event. It can be fairly considered music noise or noise pollution in this context only.

Unreasonable Noise (their term) is exactly that: a sound level that is not desirable, falling between acceptable sound levels (compliant sound emissions) and Aggravated Music Noise.

Unreasonable sound levels are acceptable inside an event or venue, but not directly outside a sensitive use such as a residence.

In a pulsating cultural landscape like Melbourne’s, the management of cultural sound, such as music, should be seen as managing competing social and cultural interests, not as a pollutant to be managed and, if possible, reduced to inaudible levels.

Those competing interests need to consider the community’s right to collectively enjoy and participate in its culture (as required by Section 11 of the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities for which the Australian Government is a signatory), as well as a resident’s right to sleep and enjoy their home. To achieve this, we need to start designing and dynamically managing our soundscapes.

This is a significant shift from the rigid thinking embedded in the current noise regulations of strict, one size fits all, statewide fixed limits.

Currently, hard dB limits are dictated for indoor venues, outdoor venues and events.

The discussion paper referenced above addresses outdoor venues and events only. It recognises that many events on public land are either over-regulated or the current permit system is a bad fit, resulting in an onerous application process and arduous regulation for the event profile. In particular:

· New Year’s Eve celebrations. Midnight Fireworks and music played late.

· The musical component of the Anzac Day dawn service. Bagpipes and the Last Post played very early in the morning.

· First peoples Australia Day dawn ceremony with music played very early in the morning.

· Weekend Night Markets. Music can exceed concert levels, and music can occur over a period of more than 8 hrs on a single day.

· Cultural Food Festivals. Music can exceed concert levels, and music can occur over a period of more than 8 hrs on a single day.

· Charity Fun Runs with music played in short bursts very early in the morning

The current environmental noise regulations allow for two permit types:

· LO5 -Operation outside of hours or extended operations.

o Private land. Operations outside the standard operating hours of between 12noon to 11 pm on any day or lasting longer than 8 hours.

o Public Land. Operations outside standard operating hours of Monday to Saturday between 7 am to 11pm, and on Sunday or on a public holiday between 9 am to11 pm or a concert on a Monday to Saturday 7 am to 12 noon, or on a Sunday and public holiday from 9 am to 12 noon or lasting longer than 8 hours.

· LO6 - Conducting more than 6 outdoor concerts per financial year.

o Where a concert is held at a location where 6 concerts have already been held in a financial year.

The permits are issued by the EPA.

The proposed exemption of the Anzac Day dawn service and the First Peoples Australia Day dawn ceremony is justified by their high social/cultural significance.

Although their high social/cultural significance is true and a factor, the same is true of all musical events, as they too are an expression of our culture.

Their exemption is better justified because music entertainment is not the focus, it is only played for a short duration, and they are free community events. There is no need to imply a hierarchy of cultural importance.

Permit Exemptions for Cultural Food Festivals, Run Runs, and Night Markets should be decided on their merits (likely to be high) and their community support. A commercial flea market selling imported plastic toys with carnival rides, emitting loud, distorted music, should perhaps not receive permit exceptions, as opposed to an annual African or Latin festival that has live music stages, which should.

Local Government should manage Soundscapes.

The best-placed organisation to manage soundscapes and balance the community’s competing needs is local government. Other events should also be assessed on their merits, not just on the current regulator’s statistically derived categories.

As soundscapes are place-specific and complex, environmental sound regulations should also allow local governments to reduce standard sound level limits in specific places for specific events with low annual frequency. This would allow for music and other cultural sounds to temporarily exceed the sound levels dictated by the environmental noise regulations in the Unreasonable Sound range for a specified period of time and by a specified dB amount. Local government should be able to vary permit conditions or issue permits with its own regulatory settings for event times, duration, and sound levels.

This would facilitate street festivals such as the St Kilda Festival, the Sydney Rd. Festival, the former and proposed revival of the Brunswick St Festival, and other urban and regional community festivals. It would also assist councils in managing dedicated outdoor event spaces through their own permitting processing.

Live Music Precincts

Live Music precincts can be defined in the VPP. The Allen Labour Government has promised to introduce an overlay in the VPP to help define live music precincts in a new section - Cultural Places, moving it from its current location in - Amenity, Human Health and Safety.

This could facilitate nuanced soundscapes management within the framework of cultural significance if the environmental noise regulations were brought into line with the new VPP changes.

The best-placed organisation to manage the soundscapes of a live music precinct and balance the community’s competing needs is again, local government. However, local government does not have the power to override environmental noise regulations (Regulation 122) unless enabled explicitly in the VPP.

The EPA lacks the resources and interest to micro-manage live music precincts and outdoor event spaces. They have also been effectively absent in this space since the current regulations were introduced about five years ago, issuing only standard permits (LO5 and LO6) and logging complaints.

A new set of regulatory tools and standards needs to be developed to be dynamic and simple without compromising effectiveness. Such a tool set needs to be able to adjust acceptable sound levels according to a soundscape’s context and the community’s needs.

For instance,

- The default acceptable sound level for music venues and live music precincts should be lowered at times when schools hold their annual fetes and when street or other festivals with live music are held.

- When schools or child day care centres are not open, a live venue can increase its sound emissions.

- The specific exemptions for iconic Live Music Venues in exceptional circumstances. Historic heritage buildings with a long history of hosting live music, such as The Tote, Night Cat, Thornbury Theatre or the Myer Music Bowl, are examples that need to be specifically considered. They may simply not be able to be soundproofed sufficiently to meet the existing noise regulations due to structural, heritage, or building cost constraints.

A compromise endorsed by the responsible authority would have to be reached to allow the venue to continue its operation. Legal security is vital to enable investment in the live music industry.

Currently, the EPA appears uninterested in playing this role. A process managed by councils achieving these balances should be enacted and defined. This way, venues can have legal certainty whilst achieving the best possible outcome for all stakeholders involved in the process.

This may also involve soundproofing installation on an affected residence, but paid for by the venue. Currently, this practical and sensible solution would not make the venue legally compliant.

A Better Sound Measurement and Management Methodology

A new sound management tool is needed in EPA’s noise protocol. It needs to be simple, emissions-based and fit for purpose. Venues need to be able to take sound measurements of their venue and understand them so they can manage the music sound emissions for which they are responsible.

The current EPA music noise protocol and regulations are inflexible, complex, and require an acoustician to measure and analyse the sound measurements necessary to assess compliance. The EPA’s regulatory framework is impossibly to complex. Venue owners and event organisers would need degrees in physics, law, and philosophy to understand them. It is not fix for purpose.

The current regulations are very similar to the original ‘music noise’ protocol - SEPP-N2, which was introduced back in the 70s. It was never intended to be used in a dynamic urban context to balance competing social and cultural interests. However, it is excellent in the planning context when ascertaining and designing soundproofing solutions for proposed residential developments and new greenfield live music venues. Its role should be restricted to this context and replaced with a simpler system.

A Better Live Music Emissions Standard.

A level of music sound at a fixed distance should be used as a benchmark for the acceptability of venue music emissions, with a buffer of 11 dB depending on circumstances. That would place the dB range within what is currently considered compliant and under what is defined as Aggravated Music Noise in the current regulations.

This can be achieved by taking two sound readings in dB(C ) over 15 minutes. One on the other side of the street (say 8m -10m away from the venue) and a second reading at a further known distance. As the background sound is the same in both measurements, it is cancelled out in the calculation, deriving just the music sound component at the first point.

The Brisbane City Council uses an emissions-based standard in the Valley. This is a single dB (C ) measurement that includes background sound and music sound. This is simpler but less accurate than what is proposed in this paper, although it’s worth reviewing its merit.

The acceptable sound level should vary depending on the time of day. The current regulations allow for two periods, but there really should be at least three periods - Daytime (up to 7 pm), early evening (7 pm until 1 am) and post 1 am.

The rationale for these is that during the day, no one is sleeping, and this is when outdoor festivals and events occur. Variable and flexible acceptable levels could be defined, depending on the circumstances as necessary.

Almost all live music in live music venues occurs between 7 pm and 1 am. In reality, it’s more like 6 to 12 midnight. Most people are not sleeping when live music is performed. A stricter yet flexible range is needed, again depending on context and circumstances.

Dance music (DJs) can go on past 1 am into the early hours of the morning. Everyone is asleep past 1 am, so the strictest standards should apply with no need for regulatory flexibility.

EDM has a different sonic footprint than live music played by bands. Hence, it needs to be managed differently, as it is bass-heavy with a consistent pulse. In some ways, it’s easier to manage the overall level because there is no stage sound, and it is controlled by a single master fader. A stricter standard is needed in this context, particularly after 1am. In a live music precinct, all EDM use would be limited to indoor venues, but for some rural music festivals, exemptions may be required (Meredith / Golden Plains, Falls Festival).

Specific values of standard sound level limits need to be separately considered to take account of the difference between:

- dB(A) and dB(C),

- the absolute dB(A) levels in the regulations that contain music and ambient sound levels compared to dB(C) levels that only contain music sound and,

-the distance of sound measurements taken from the music sound source.

The adjustment of the dB values would need attention to align existing sound levels in the regulations with any changes to a different dB weighting.

Exemptions

Exemptions are required for Sound Marks. These are typical heritage sounds that exceed the noise regulations but are culturally or historically significant. The best examples are church bells, but could include sounds like steam engines, fireworks, historic cannon fire (the 21-gun salute), etc.

Sound Marks could be used to cover exemption for both the Anzac Day Services and the First Peoples Australia Day Dawn Ceremony, both of which occur at significant specific times and locations.

VPP tweaks

Finally, the agent of change is required to take responsibility for the cost of building works required for soundproofing. This can currently be the venue or the permit applicant for the development of a residential building.

This should be sharpened up. As the agent of change in a live music precinct is no longer the venue, some residents need to take on the responsibility of soundproofing if required. This is because the current regulations stipulate that the measurement point is located within the habitable room. The scenario involves existing historic building stock predating the introduction of Agent of Change.

Regardless, these situations should have been resolved by now and will only appear when new owners buy into these buildings or lease them when their amenity expectations are not met. It would be of great benefit if a buyer-beware statement were to be included in the planning report that forms part of section 32 for all contracts of sale for properties that are sold in live music precincts.

Finally, the Victoria building code should include a section on sound attenuation standards for residential buildings designed in live music precincts and when a residential building is to be built 50m or less from an existing live music venue. Such standards would help reduce the design costs of future residential developments, alleviating the need for bespoke site-specific soundproofing design solutions. These standards can be copied as is from the Brisbane City Council’s planning scheme.

Further weaknesses with the EPA’s Current Noise Protocol.

The current EPA noise protocol for music uses background sound measurements as part of the methodology to determine compliance. In the night-time period, the difference between music sound measurements taken over 15 minutes and background sound, cannot exceed 8 dB in any octave.

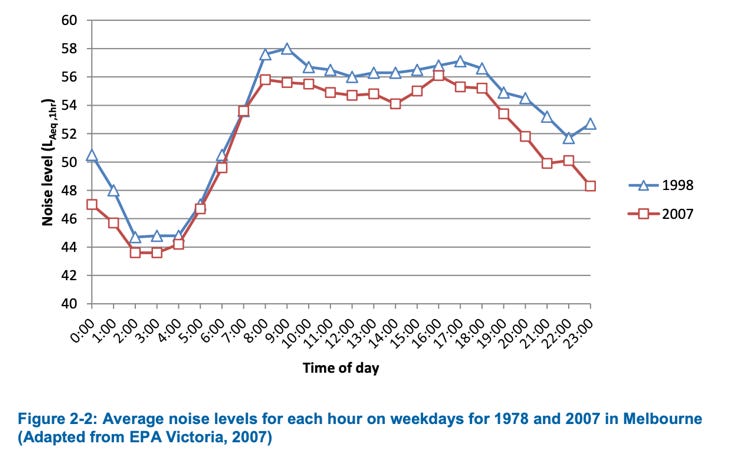

However, the time when the background sound measurements are taken can make a huge difference in the results.

For example, at an iconic Melbourne Music Venue I will not name, two acoustic reports prepared by two different acousticians yield very different results. The sound measurements were taken at the same place, but the background sound was taken at very different times of the night (1103pm and 3am). The variance in the result is in the order of 40 – 60%!

As can be seen from the graph produced by the EPA, it shows the variance of background sound over 24 hours. The difference between the two background measurements between the two acoustic consultancies can be read from the chart. In other words, the difference between the noise regulation analysis can be directly attributed to the measurement times of the background sound measurement.

This is why an alternate method based on two dB (C) sound measurements taken at known distances from the venue - where background sound is mathematically cancelled out because it is equal in both measurements- is a better, simpler, and fairer methodology.

Conclusion

The complexity and error-prone nature of the current noise protocol’s assessment methodology, along with its strict, inflexible compliance interpretation, are setting live music venues, festivals and events up to fail.

Buried deep in the discussion papers, Appendix 2, section 6, “Community Value” is acknowledged through several separate references.

“Outdoor entertainment events and music festivals have a cultural, social and economic value. Events provide an opportunity to display culture and foster social connectedness, which are positively associated with general wellbeing 44. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that the degree of noise annoyance can be influenced by subjective and attitudinal factors 45. A positive appraisal of an outdoor music event can be associated with factors of cultural contribution, whether the event is free and accessible to all ages, supports a charitable cause or an awareness raising objective 46, or is economically desirable 47. Therefore, some jurisdictions vary noise restrictions or grant exemptions from permit requirements to reflect broad community support and create a more enabling regulatory environment for these events 48.”

Judging by this paragraph, it seems the EPA understands the social and cultural context of their regulations and that flexibility is needed. Why then, the resistance to “a more enabling regulatory environment”. It is hard to fathom.

However, it is encouraging to see that both the planning scheme and the environmental regulations for music ‘noise’ are under review but the siloed thinking between the responsible ministries is problematic. For better results, both the VPP’s sections on live music and the environmental noise regulations need to be considered holistically in the reform process.

If only the Victorian Governments Live Music Round Table still existed to facilitate, in conjunction with the music industry, pan-government regulatory reform…

Written by Jon Perring, 20th November 2025.